Abondoned property expert shares some solutions with Duluth

No one person really knows how many abandoned properties are in Duluth. Joe Schilling guesses that there are about 2,000 abandoned and vacant properties in Duluth. “The good news,” he said, “Is that they are scattered. What is really great is that you are talking about this issue now.” Schilling is a Professor in Practice at Virginia Tech’s Metropolitan Institute and Director of Research and Policy for the National Vacant Properties Campaign.

If governmental departments share information with each other, Duluth has a good chance of stopping the spread of vacant and abandoned properties into whole blocks. “It is really critical to get the information. Information is power,” said Schilling.

Schilling spoke to a group of concerned Duluth residents at the Central Hillside Community Center on Wed., Sept. 27. He and Dan Kildee, also of the National Vacant Properties Campaign, had spent the day before touring Duluth with Ben Small and Kim Crawford of CHUM Gabriel Project, an initiative to work on issues of poverty.

Schilling and Kildee met with Duluth LISC (Local Initiative Support Corporation), the City of Duluth, St. Louis County, Churches United in Ministry, the Housing and Redevelopment Authority of Duluth, Northern Communities Land Trust, and other nonprofit partners and neighborhood residents to develop effective solutions to the problems of property abandonment. Kildee is the treasurer of Genesee County (Michigan). Flint is a city in Genesee County, which lost 80,000 people. There are blocks of abandoned houses. Duluth does not have a situation as bad.

Schilling said that Duluth was on the cusp of turning worse or getting better. He felt that Duluth had the ingredients to turn the abandoned housing situation around and was in a better position than some of the other cities he has worked with. Those cities include: Philadelphia, Pa, Flint, Mich., San Diego, Calif., and Tucson, Ariz. and Louisville, Ky.

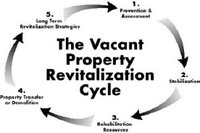

Schilling listed five essential ingredients needed to fight the spread of abandoned property: community catalysts and urban pioneers, leadership and vision, variety of strategies and tolls, systematic program management and convergence and coming together. He told the group of about 15 community members at the meeting, “Congratulations! You guys are doing wonderful work.” He went on to say, “We’ve been really impressed.”

Schilling showed the group a slide show, which explained the continuum from green to brown of vacant properties. Brownfield’s are industrial areas, which have been abandoned due to environmental pollution. Greyfields are business districts, like shopping malls, which have been abandoned.

The broken window theory is one of the main reasons why communities want to prevent abandoned property. Once an area is known as abandoned, windows become broken and it becomes a haven for crime and drugs, fire and a public hazard.

If communities have a policy in place to deal with abandoned property, then when a vacant property pops up, the staff of a city or governmental department knows how to deal with it. Sometimes different departments may be aware that a building is abandoned, but there is no communicating between the departments. For example, the water department may be aware that no water has been used, the city assessor’s office knows that the taxes haven’t been paid in years, and the police or fire department have been dealing with the building, but no one agency has taken the initiative to do anything about it because they are not sharing information together.

Some cities have started ecology and housing courts. For example, two days a week judges who are used to dealing with abandoned and vacant properties listen to cases. The fees from the civil penalties are paid to the city, which can in turn use them to fund prevention programs.

Action steps Schilling suggested included: adopting and administrating a rental inspection, registration of vacant property ordinance, creating a vacant property coordinator, education and training on how to be a better landlord, and reform of existing building and zoning codes.” You don’t need to go to St. Paul,” he said, referring that cities in Minnesota have the power to enact their own codes.

An effective method in some towns has been a “shaming sign.” A huge sign is posted on the vacant property listing the owner of the property and the code violations. Sometimes the press is called as the sign is being posted. Schilling said the shaming signs have been effective. Within few days of the signs’ posting, the violations have been remedied. There are other ways of shaming people. He talked of a doctor who owned abandoned properties, people stood on the sidewalk in front of his practice and said, “Dr. Jones is a slumlord here is a photo of his property.”

In a separate interview, Pam Kramer, Senior Program Director of Duluth LISC said, “What I am excited about is the opportunity to work together on a comprehensive approach. I was very impressed with the level of commitment (by governmental officials) to work on the issue of blighted property and vacant land.

(Duluth LISC secured $15,000 in federal Department of Housing and Urban Development funds from national LISC to provide technical assistance to address this issue. In addition to this technical assistance visit, a series of “virtual brown bag” training sessions and other consultation will be provided. The National Vacant Properties Campaign is a collaboration of four leading national organizations: Smart Growth America, Local Initiatives Support Corporation, the International City/County Management Association, and the Metropolitan Institute at Virginia Tech.)